Trapped atoms could advance quantum computing

Rubidium atoms trapped by laser beams could herald dawn of quantum supercomputers that can solve problems far, far quicker than today's hardware.

Atoms held in energy wells created by laser beams could hold the key to ever faster supercomputers that could solve mathematical problems that today's fastest computers could not solve in years.

Scientists working at the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have trapped thousands of atoms in laser beams and managed to make them swap spins with partnered atoms simultaneously. This spin swapping lays the foundation for logical operations that form the backbone of computing.

The repeated exchanges only last around 10 milliseconds but could herald the dawn of extremely fast quantum-based computers. The process of swapping is a way of creating logical operations such as an if/then statement. For example, if two atoms or quantum bits have opposing states then they should exchange values.

The experiment used 60,000 rubidium atoms in a Bose-Einstein condensate, a special state of matter in which all atoms are in the same quantum state. According to the scientists, atoms swap their internal spin states with a partner atom. Each atom can "spin up" or "spin down", mirroring the ones and zeros of binary.

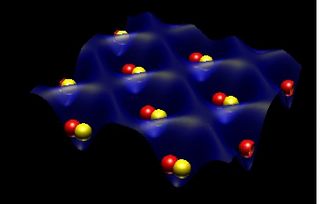

Led by Nobel Laureate William Phillips, the NIST group used three pairs of infrared laser beams to trap the atoms within a three-dimensional grid. The lasers created two horizontal lattices overlapping like two meshed screens, one twice as fine as the other in one dimension. This created energy "wells" which trapped atoms.

The scientists put a single atom into each well. These atoms were either spin up (or one) or spin down (or zero). They then forced the atoms to pair up into the same well where they could interact.

When two such identical atoms are forced into the same physical location, quantum mechanics imposes a specific type of symmetry (only two of four seemingly possible combinations of quantum states are allowed). Due to this restriction, the combined atoms oscillate between the condition in which one atom is one and the other is zero, to the opposite condition. This behaviour is unique to identical particles.

Get the ITPro. daily newsletter

Receive our latest news, industry updates, featured resources and more. Sign up today to receive our FREE report on AI cyber crime & security - newly updated for 2024.

When the atoms swap their spins they pass in and out of quantum entanglement. This entanglement makes quantum computing an attractive proposition as it could allow really powerful computers. At the halfway point each atom's spin is uncertain and, if measured, could be either up or down. Regardless of the result of measuring one atom, the other in the pair would be in the opposite spin. According to one of the scientists involved in the experiment, Trey Porto, this is the first time that quantum mechanical symmetry, or exchange symmetry, has been used to perform such an entangling operation with atoms.

"This is the first time these spin-entangling interactions have been demonstrated between pairs of atoms in an optical lattice," said Porto. "Other research groups have entangled atoms in lattices as extended clusters. By isolating pairs, we can focus on the simplest units for quantum logic."

Porto said that the current experimental set-up is not directly scalable to an arbitrary computer architecture as it performed the same spin-swap in parallel for all pairs of atoms. If pairs of atoms in the lattice could be individually manipulated then the process could scale.

He said that researchers are now looking at ways of refining this process and improving the reliability of each step. They also hope to complete the logic operation by separating atoms after they interact.

Rene Millman is a freelance writer and broadcaster who covers cybersecurity, AI, IoT, and the cloud. He also works as a contributing analyst at GigaOm and has previously worked as an analyst for Gartner covering the infrastructure market. He has made numerous television appearances to give his views and expertise on technology trends and companies that affect and shape our lives. You can follow Rene Millman on Twitter.