Windows 7: The most accessible Windows yet?

Microsoft has taken pains to make Windows 7 a better experience for everyone, but is the new Windows ready for users with disabilities, right out of the box?

Windows 7 will be with us in just a few weeks and it's generally accepted that the new operating system is good news for end users and IT departments, whether they opted for Vista or not.

However, the latest Windows could also bring benefits for some more specific groups of IT users: people with visual or hearing impairments, those with impaired mobility, or those with dyslexia, cognitive impairments or learning difficulties.

Given that the Disability Rights Commission estimates that this might cover up to 13 per cent of the UK workforce is, this could be another good reason for IT departments and individual users to upgrade.

Accessibility tools

Of course, accessibility tools are nothing new. Windows has been improving access for users with disabilities since the release of the Active Accessibility SDK for Windows 95 in 1997.

Windows 98 was the first version to bring more advanced features into the core OS, most notable a screen magnifier for people with visual impairments, while Windows XP added a simple text-to-speech utility, Narrator, plus an on-screen keyboard.

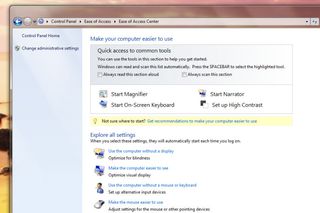

Even Vista bought some improvements, adding native speech recognition and reorganising everything into one Ease of Access Center control panel.

Get the ITPro. daily newsletter

Receive our latest news, industry updates, featured resources and more. Sign up today to receive our FREE report on AI cyber crime & security - newly updated for 2024.

However, Windows is still far from an all-in solution for users with disabilities.

Many still need third-party applications to make the operating system work for them, particularly in the workplace. For example, most blind users still have to rely on screen-readers like Jaws, HAL and WindowsEyes, which convert text into speech or provide audible descriptions of elements on the screen.

Meanwhile, most visually impaired users opt for third-party magnifiers like WinZoom, MAGic or Lunar over the built-in Windows option. When these products can cost upwards of 600, this represents a major expense, whether for them or for their employers.

Windows 7, then, offers Microsoft a real opportunity to cut down on the cost of computing for users with disabilities.

This hasn't passed Redmond by. Microsoft claims that it now regards accessibility as equal to performance or reliability as a metric by which Windows should be judged, while Michael Bernstein, development lead on the User Interface Platform team has described how his team "wanted to make Windows 7 the most accessible operating system that Microsoft has ever produced."

Features overhauled

Cheap promises, or real improvements? Well, for a start, two major accessibility features have had a complete overhaul.

The Magnifier was always a useful tool, but many visually impaired users found it counter-intuitive. While the Magnifier magnified the area around the pointer, following it around the desktop, the actual magnified display was fixed to the top of the screen. This was fine for reading text, but it could also make it hard to see exactly where you were looking.

The new Magnifier offers two additional, more useful views - a full-screen option which enables the user to zoom in and out of the desktop, the image scrolling as necessary, and a virtual lens where the display follows the pointer as it travels around.

The on-screen keyboard, meanwhile, has been overhauled to make it look and work more like the soft keyboard used by users of tablet PCs.

It's not only more attractive, it's also now fully resizable and better equipped to work for users with mobility impairments, offering basic text prediction and the option to select keys either by hovering over them with the pointer or by an ingenious, one button 'scan to' system.

These improvements might sound small, but they have the potential to make life much easier for many thousands of users in the UK.

In the most part, early feedback on Windows 7 seems favourable.

David Banes, development director of AbilityNet, a charity specialising in helping disabled users use computers, describes the new full-screen magnifier as "a major improvement for magnification" and says that the new on-screen keyboard will "make things a lot easier for people with physical difficulties." Predictive text input alone is "really going to speed up text entry for those who use onscreen keyboards."

Perfect focus?

This positive vibe is shared by Stuart Barron, a member of the British Computer Association of the Blind, who feels the new Magnifier is a great help when navigating the Windows desktop. Its one downfall, Barron notes, is that "the software doesn't follow the typing cursor, so as a touch typist it slows the user down." This, Barron feels, is a shame. This feature, if fixed, would save him around 200 to 300 on upgrading his existing third-party software.

However, the Magnifier has one serious flaw. The new Magnifier relies heavily on Aero, the GPU-accelerated graphics system at the heart of the Vista and Windows 7 UI. Unfortunately, Aero is incompatible with a specific theme High Contrast which is often employed by people with visual impairments.

As a result, anyone who wants to use the High Contrast theme is stuck with the old Vista-style Magnifier and not the new one. Making two features the users with visual impairments might need mutually exclusive might seem like thoughtlessness, but the fault isn't completely Microsoft's.

Apparently High Contrast ignores Aero in order not to upset third-party screen reader programs that do their work through the original Windows graphics system (or GDI). Of course, this begs the question: why not make an Aero-specific High Contrast theme?

Under the bonnet

Luckily, Windows 7 bring some other benefits to user with disabilities, albeit less immediately obvious ones.

Users with impaired mobility rely on a range of assitive technologies to make Windows work for them, ranging from voice recognition apps to specialist mice, trackballs and trackpads to controllers that allow those with severe restrictions to move a pointer with lip movements and 'sip and puff' clicking.

Windows Vista introduced a UI automation API to give manufacturers of these devices more scope to drive Windows applications through programmed responses and so create a more intuitive and intelligent interface for their users.

Windows 7 enhances this API's performance, and enables developers to work with it not just through the .NET framework but through regular C++ code. This should help them make their products more flexible and powerful in the future. Windows 7 also supports new utilities that enable software developers to check their code and UI for accessibility or UI automation issues.

Meanwhile, Windows 7's new focus on backwards compatibility is another bonus, particularly the introduction of the Windows XP mode. This ensures that the full range of existing AT hardware and applications should still work in the new OS." Those sorts of thing are quite important to disabled users," says AbilityNet's David Banes.

"If they have a third-party solution they've been using, they're always very anxious about upgrading to a new operating system in case they lose that feature. If you take away something that someone is familiar and confident with - particularly if it makes it difficult for them to their job - it causes a high level of anxiety."

For Banes, Windows 7's native support for touch control is equally important. The standard keyboard and mouse interface, which most of us accept as standard, can be a real barrier to people who have physical disabilities, have learning difficulties, or simply have no previous experience with computers.

A touchscreen interface can remove that barrier. "The fact that what you see is what you touch is what you do is actually much, much easier for them to understand and use," he said.

There are some areas where Windows 7 certainly could do better. Another BCAB member, Chris Hallsworth, applauds Microsoft's efforts to improve accessibility, particularly small touches like the fact that Narrator can more easily be configured to speak at startup.

Yet at the same time, Narrator's inability to speak most webpages in Internet Explorer or other browsers means he's forced to stick with third-party software.

Other users find Narrator's unstructured gush of speech - covering every area and clickable item on the page - confusing, and the voice it uses unnatural, or even incomprehensible. Third-party products, like Freedom Scientific's JAWS, still offer more natural sounding speech and a selection of voices, while also working with Braille displays, which convert the text into Braile characters that the use can feel.

"I think Narrator still needs work," said Banes. "But what Microsoft has done is put funding into the open-source screen reader, NVDA" - a free, downloadable open-source screen reader supported and funded by, amongst others, Microsoft, Adobe, Mozilla and Yahoo. NVDA can handle a greater range of web content, with plans to expand its scope to Adobe's Flash format as well.

Unquestionably, Microsoft has work to do if it wants to make Windows accessible to everyone, straight from the box, and, for now at least, third party specialists have plenty of opportunity to offer a better experience.

However, Redmond is, at least, getting part of the way there. Arguably, the very fact that such solid accessibility features are built into the core OS is a good thing in itself.

"It will give people confidence that assistive technology actually can help them, and that those applications and customisation will work for them," added Banes, hoping that this will go beyond just those people who would normally consider themselves as having disabilities.

"Everyone should be customising their desktop to meet their own needs," he says.

Next time you find yourself squinting at your high-resolution screen, give that some thought.

Stuart has been writing about technology for over 25 years, focusing on PC hardware, enterprise technology, education tech, cloud services and video games. Along the way he’s worked extensively with Windows, MacOS, Linux, Android and Chrome OS devices, and tested everything from laptops to laser printers, graphics cards to gaming headsets.

He’s then written about all this stuff – and more – for outlets, including PC Pro, IT Pro, Expert Reviews and The Sunday Times. He’s also written and edited books on Windows, video games and Scratch programming for younger coders. When he’s not fiddling with tech or playing games, you’ll find him working in the garden, walking, reading or watching films.

You can follow Stuart on Twitter at @SATAndrews.