Firefox: The problems ahead

One of the reigning mass market champions of open source software appears to have hit choppy waters. With Firefox 3 on the horizon, IT PRO finds out what's happening with the world's favourite non-Microsoft browser.

Considering that it only launched its web browser officially back in November 2004, the Mozilla Foundation has every reason to pat itself on the back over the news that Firefox has now been downloaded for the 400 millionth time. Whichever way you spin it, that's some number.

A tangible, deserving champion of the open source movement, Firefox has been widely credited with achieving something many thought doubtful: not only has it delivered a product that instantly showed up the failings of existing alternatives, it's seriously hit its Microsoft competitor. Whereas the web sector was once Microsoft dominated to a level of over 90 per cent, it's the giant of Redmond that has been on the back foot in this sector for much of the last three years.

Domination

And not only does the most popular of them all, Firefox, continue to grow market share, its numbers are showing just how far its come in its short life. According to numbers from web survey institute XiTi Monitor, at the start of July, Firefox accounted for 27.8 per cent of web browser use in Europe, even soaring up to 47.9 per cent in Slovenia and 45 per cent in Finland. The crucial barometer though is the rate of growth, with a 6.9 per cent increase across Europe in Firefox use over the past twelve months, and indicators suggesting no end yet to the browser's mounting take-up.

Issues

And in a further consideration, it's worth stopping to consider the figure that's being openly discussed by Mozilla on its wiki, where it openly admits a need to improve its retention rate.

Currently, of the people who actually download the Firefox software, it's only around a half who get round to installing it (although, to be fair, that's a figure that's likely to contrast well with other download-only applications). Another widely-reported statistic is that 75 per cent of those who download Firefox fail to become active users. While one in four isn't a bad hit-rate, there's obvious room for growth.

Get the ITPro. daily newsletter

Receive our latest news, industry updates, featured resources and more. Sign up today to receive our FREE report on AI cyber crime & security - newly updated for 2024.

As Mozilla acknowledges, there are some big challenges facing Firefox.

The road ahead

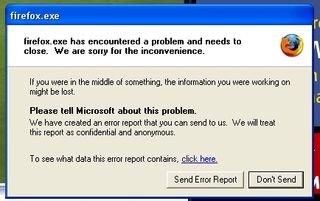

Certainly the latter point is reflected in newsgroups and forums across the world, with increasing complaints of Firefox crashing when placed under pressure. Take one of the big features Firefox brought to the mass market: tabbed browsing. It's something many now find invaluable, but ironically Firefox 2 is less comfortable with it than previous iterations. Software freezes, long waits and general hanging are all on the list of troubles. The result is that a number of users are finding themselves using one of Firefox's newer additions more often than they'd like: the recovery tool.

Many too have, rightly, criticised the browser for its surprisingly heavy demands on system memory. The idle Firefox application that's sitting open on our test laptop for instance is gobbling up 47MB of system memory, compared to a more modest 13MB for Internet Explorer. It's just one instance, but it mirrors reports that are easily findable right across the web. Surely, going back to the roots of Firefox, it shouldn't be that way round?

Yet it is. The Firefox software has a well-reported habit of eating up vast amounts of system resource that shows little sign of abating, and this can be tracked back as a cause to some of the stability issues that were mentioned earlier.

It's worse for those who regularly take advantage of the add-ons available for Firefox too, as they seem to expose themselves to a greater risk of crashing and general instability. Many of the memory leaking complaints that have dogged recent iterations of the browser have been traced back to the huge catalogue of open source plug-ins. And while there's a certain amount of goodwill associated with trying these free add-ons, the inability of the browser to remain fully stable with everything on board is undoubtedly not helpful. It should be noted that much of this is, of course, out of Mozilla's hands, as it's not responsible for the coding and implementation of the large number of plug-ins available. It doesn't make it less of a problem for an end user, though.

Chorus

Mozilla, though, is quick to refute the argument of increased bloat, although this too raises alarm bells for some who argue that if it won't even admit the problem, what hope is there of fixing it. Nonetheless, Mozilla stresses that it continually leaves features out of Firefox to keep it as smooth-running and streamlined as possible.

There's little doubt though that the smooth browser that many jumped towards three years ago is fatter than it once was. Its speed advantage over Internet Explorer in Windows has eroded of late (partly due to IE's native ties into the OS), and the advocates who worked hard to spread the Firefox word across the web may now choose instead to turn towards the growing number of open source alternatives that are existing in its slipstream. Bluntly, the thirst for a light browser that remains compliant with the vast bulk of web standards is still very much in place, yet whether Firefox fits those shoes comfortably enough is a debate that's getting ever-more vocal.

Firefox 3

Granted, that's still the case to a point, but every feature that makes the jump from optional to embedded is going to have some kind of performance footprint. Mozilla argue that it's wary of this too, and that its guiding philosophy is to only bed in features that will have an appeal to 90 per cent of Firefox's users. But even so, compared to Firefox 1.0, version three is going to be an obviously heavier, albeit more capable, beast.

In its defence, the web is a very different place in 2007 than it was in 2004, and Firefox has to react to that (not least for security reasons, which we're coming to shortly). The Web 2.0 revolution has brought with it streaming media as the norm, and Flash is an increasingly de-rigour inclusion on a mainstream website. Compatibility for this surely needs to be built into the core of the browser. Furthermore, system capabilities have similarly moved on, and much though it's an argument Mozilla wouldn't want to put, the desktop computer of 2007 can shift around a lot more work than that of 2004.

The price you pay?

While Firefox does have technical issues that need addressing and overcoming, there is a suspicion that some of the flack that it's been copping is merely the downside of the hype wave that it's been riding for the last couple of years. Much though it's been shown to be an able alternative - and even successor - to Internet Explorer, it's also proven not to be bullet-proof, and is vulnerable to the occasional security exploitation itself.

But isn't that part of the price you pay for success? The bigger the user base - and it's now well into nine figures - the more problems are likely to emerge, and the more difficult it comes to keep people happy. What's more, the criminals of the cyber world will attack wherever large numbers of users can be found, and Firefox very much fits that criteria now.

The Firefox browser then, to appeal to as broad a majority as possible, needs to include some form of protection to fend these attacks off, but inevitably starts to bulk up as a result. Appreciating that the bloat accusations aren't restricted to its security features, it's nonetheless on example of how Firefox surely has to react simply to stay vital in its market.

The fightback

More to the point, a large number of its users are seemingly content with their choice, and while frustrations no doubt abound at some of the issues we've been discussing, it's still for many a preferable option than its main competitor. As many critics cite, it's still a great piece of software, just right now it's a frustrating one.

Mozilla itself is now looking to become increasing aggressive in the way it pushes Firefox, particularly with the incoming third iteration of the software. Referring back to the declaration earlier that around half of those who download it never use it, Mozilla has earmarked this as a major opportunity, based presumably on the assumption that if someone is interested enough to download the program, it just needs one more push to get them to execute it.

On its wiki, Mozilla has thus published what it believes to be the challenges it faces, and each of them point at a strategy that's very heavily focused on mass market conversion. For instance, under the broad heading 'What's a browser?', cited challenges include 'Isn't the Internet the blue e icon on my desktop', and 'what makes a browser different from another'. You can find the full posting yourself at http://wiki.mozilla.org/Retention

This focus on broader appeal though isn't likely to sit easily with some early adopters, and a minority of them are now calling for a splinter project to go back to the roots of Firefox. This should, in theory, be possible, and perhaps the option exists for a lighter version of the software.

Yet it's still unlikely to be the link that most people click on. Because irrespective of the problems Mozilla has faced with Firefox of late, the truth remains that it's a more 'socially' popular piece of software than Internet Explorer, and that people continue to migrate from the latter to the former.

The future

But the speed and vibrancy of the web market is keeping more and more companies and products on their toes, which is why - in spite of a perceived lack of action - those heavily involved in the Firefox project are unlikely to have let the criticisms pass them by. The likelihood remains that, for the next year or two at least, Firefox will continue to grow, and continue to erode Internet Explorer's market share.

The trick then is to do what it once did best: be reactive to the demands of its users, avoid the temptation to add features for the sake of it, and crucially, to perform better than its competition. If it doesn't, this is a market that's proven many times that it's willing to put another name up in lights instead. While that's a fate that's likely to escape Firefox, especially in the short to medium term, it's a hell of a long way down...