How to solve Australia’s tech talent shortage

Australia’s border closures have exacerbated a pre-existing skills shortage, so how can the country help its technology sector attract and retain the right workers?

This article originally appeared in issue 20 of IT Pro 20/20, available here. To sign up to receive each new issue in your inbox, click here

While the pandemic has accelerated the shift to digital transformation for businesses around the world, it has also put additional stress on the tech sector’s available talent pool as more workers are needed to fill essential roles. This applies, in particular, to countries like Australia who, despite enticing around 4,000 new arrivals a week through decades of immigration, has suddenly found itself facing a growing tech skills shortage as borders remain closed during the pandemic and its aftermath.

Help wanted

The country has seen a rapid increase in the amount of IT projects in motion at any one time in recent years, according to Verena Colling, a recruiter at Hays Globalink. Many of these projects were started with digital transformation in mind, adds Colling, whose role is focused on helping IT, technology, digital, and marketing candidates find the right jobs and relocate to Australia or New Zealand.

Colling also cites the acceleration of cloud migration as another key driving force, especially technologies such as AWS and Azure, which has led to an increased demand for cloud engineers. Full-stack and front-end developers, DevOps and UI and UX designers, as well as cyber security engineers and data scientists are all also in high demand right now in Australia.

To combat this growing tech skills gap, employers are more willing to hire talent from overseas than they were pre-pandemic, according to Colling. “However, due to COVID-19 restrictions there has been difficulty in obtaining visas for professionals other than expats who are returning,” she explains.

That said, the Australian government has widened its Priority Migration Skilled Occupation List - which is a list of 44 occupations which fill critical skills needed to support the country’s recovery from the pandemic - and does its best to fast-track visas for these roles.

This list, Colling says, includes various tech and IT occupations so employers can now hire from outside Australia and sponsor workers who are typically given a four-year visa. But more can still be done, with Colling adding: “Ideally – the priority list needs to be expanded to reflect the talent shortages across the whole of technology.”

Get the ITPro. daily newsletter

Receive our latest news, industry updates, featured resources and more. Sign up today to receive our FREE report on AI cyber crime & security - newly updated for 2024.

Supply and demand

One big challenge for Australia will be how it competes with the rest of the world when it, too, is competing with the same shrinking talent pool, according to Louise Francis, IDC ANZ’s country manager and research director.

Businesses seeking scarce talent have turned to remote workers in order to tap into talent further afield, including internationally, Francis says.

“Virtual employment is becoming more and more common, particularly in the tech industry where some roles are advertised as ‘work anywhere’ and get paid in US$ - the best of both worlds for talent seeking to broaden their horizons without leaving home,” she underlines.

However, this is fast becoming a problem in itself. Francis says it is a “double edged sword” with local Australian talent also being approached by overseas firms, further exacerbating the original skills shortage problem.

That said, it’s important to remember that Australia’s recruitment issues existed pre-pandemic, says Helen Souness, The Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) Online’s CEO. Indeed, she believes that the border closures have simply amplified things to the extent it’s just now, simply, an even bigger issue.

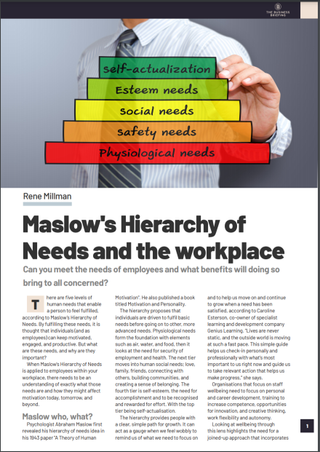

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs and the workplace

Sample our exclusive Business Briefing content

“Underpinning the talent shortage is the fact that not enough Australians have the technical or digital skills we need to be seen as an innovation leader,” she explains.

A recent RMIT Online report ‘Ready, set, upskill: effective training for the jobs of tomorrow’ suggests that Australia needs 156,000 new technology workers by 2025 to keep pace with the rapid transformation of businesses and to avoid jeopardising the country’s future economic growth.

To deal with this, Souness suggests that employers support existing Australians in the workforce by providing more on-the-job training, and establishing a culture where upskilling is valued and not thought of as a “hobby”.

There also needs to be a clear pathway leading out of the impact of the pandemic, Souness stresses. In addition, she believes it is vital that the broader market, both on and off Australia’s shores, is made more aware of why the country is a “booming innovation hub” and why it’s an ideal place to grow a career in digital literacy.

Migration, migration, migration

Cyber security and software development has been impacted by the talent shortage in the local tech sector, according to Pieter Danhieux, co-founder and CEO of Secure Code Warrior. Since the pandemic began, he says that the talent usually arriving from Europe or the US - which brings “knowledge and decades of skill” - is simply not happening anymore.

This means everyone is “chasing the exact same talent pool of cyber security people” which leads to salaries in the region inflating, Danhieux explains.

“If you know any people in the UK that are developers or in cyber security, we want to import them, help them settle down here,” he adds.

Secure Code Warrior has doubled its headcount in the last 12 months, but because Danhieux couldn’t find the right software developers in Australia, he was forced to recruit staff from Iceland and the US, where “there’s a bigger talent pool”.

To help resolve the problem going forward, Danhieux suggests getting everyone vaccinated, opening the borders, and then convincing foreign workers that Australia is “actually a great country to live in”.

Following that, he believes there’s an opportunity to reskill and retrain the existing workforce into cyber security and software development roles. He says you can take IT workers, or even those who have never worked with computers, and teach them how to write code and become developers or even analysts.

As well as affecting larger firms, the shortage has also adversely impacted Australia’s startup ecosystem. There’s been an increase in very skilled workers returning home post-pandemic and building high-quality, successful startups locally, according to Keith Davison, partner at Dovetail.

“Whether it’s software engineering, product, cyber security, or cloud, the talent available in this space just isn’t enough,” says Davison. “As a result, it’s increasing the cost of labour and creating a delta between the rest of the workforce.“

As such, companies have had to get creative to entice and retain their talent, which usually “involves bigger pay cheques and company perks” which most startups can’t afford, he adds.

Davison believes that Australia has to shore up its internal pipeline of tech talent to continue delivering results and that the pandemic has caused the region’s local tech-talent pool “to dry up even more” due to the border closures.

“The general movement of people, through migration and immigration, are aimed at helping solve talent shortage issues by bringing international talent into the country,” he further highlights.

Finally, Australia’s local, state, and federal governments need to do more about the issue, too, according to Davison. That, he suggests, could be allowing skilled workers to enter the country for work or offering more education domestically to equip the population with the tech talent the country desperately needs for long-term economic growth.

Zach Marzouk is a former ITPro, CloudPro, and ChannelPro staff writer, covering topics like security, privacy, worker rights, and startups, primarily in the Asia Pacific and the US regions. Zach joined ITPro in 2017 where he was introduced to the world of B2B technology as a junior staff writer, before he returned to Argentina in 2018, working in communications and as a copywriter. In 2021, he made his way back to ITPro as a staff writer during the pandemic, before joining the world of freelance in 2022.