How to learn Emacs

This tool may be old, but it's the Swiss-army knife of software

Spend a few decades using computers for work and you'll shell out hundreds of pounds or more on graphical text editors and personal organisation software, not to mention browser extensions and cloud-based services. They usually do some things right, but few if any do it all. Their shiny interfaces are attractive to a touch-and-swipe generation, but they trade off flexibility for ease of use. Instead of bending them to your will, you have to work around them. For real flexibility, you have to go back to a program conceived before the first PC ever shipped.

In software terms, Emacs is a cross between a Swiss Army knife and an industrial forklift. It dates back to 1976 as a collection of macros written for TECO, a text editor that itself dates back to the sixties. It took on different incarnations until Free Software Foundation founder Richard Stallman created an open source version called GNU Emacs in 1985. That version is still one of the most popular implementations of Emacs, it costs nothing to use, and it's completely open source.

At its heart, emacs is a text editor, but with such a configurable and extensible feature set that you can use it for anything. You can even program it using a built-in version of the Lisp language called Emacs Lisp (Elisp). Sure, you can configure Microsoft Word using an underlying programming language too, but Emacs goes further. People have used Elisp to create everything from email clients through to RSS readers and even web browsers built directly into Emacs. You can use it as an integrated development environment (IDE) to code with, or as a personal organiser.

Let's do something simple in Emacs: we'll create a document that runs its own code to insert the current date. Begin by installing the program. You can get it from the GNU downloads page, or if you prefer the command line, then use your own package manager (e.g. on Debian/Ubuntu Linux distros: sudo apt-get install emacs).

The Mac also has extra versions like Aquamacs and Spacemacs, which use Mac-specific features and key bindings. You can download and install most of these systems as binaries. Purists at the other end of the spectrum can also compile their own version of GNU Emacs from source code.

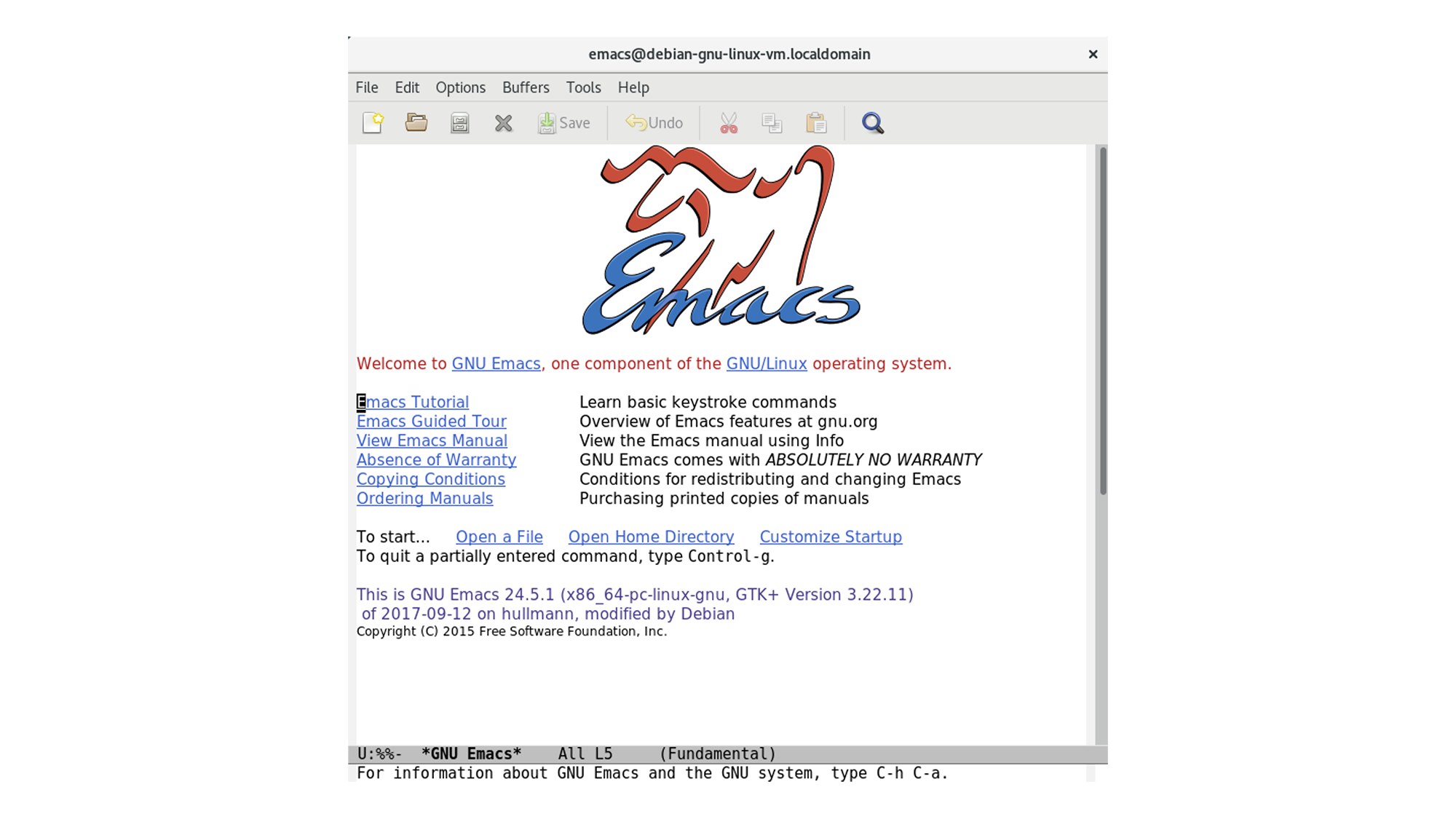

Open Emacs and you'll see this screen showing the default splash page:

You can run through the tutorial on your own by moving the cursor over the highlighted Emacs Tutorial section and hitting return. It's worth reading at least the first few pages now so that you understand how to move around in the system.

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

RELATED RESOURCE

Feeding the content-data loop

Like data, content must be well-managed, trustworthy, and secure

After checking the tutorial's first few pages, start by creating a file. To do this, you need to understand the Control and Meta keys. Control is a key (typically mapping to the CTRL key on your keyboard) that you press in conjunction with other key combinations to execute basic editing commands. C-p (that's CTRL-p), C-n, C-f and C-b move the cursor up, down, right, and left respectively. You can use the arrow keys instead, but the point of Emacs is to move your hands from one place on the keyboard to another as little as possible. It's designed to make you faster over time as your muscle memory absorbs the arcane key combos.

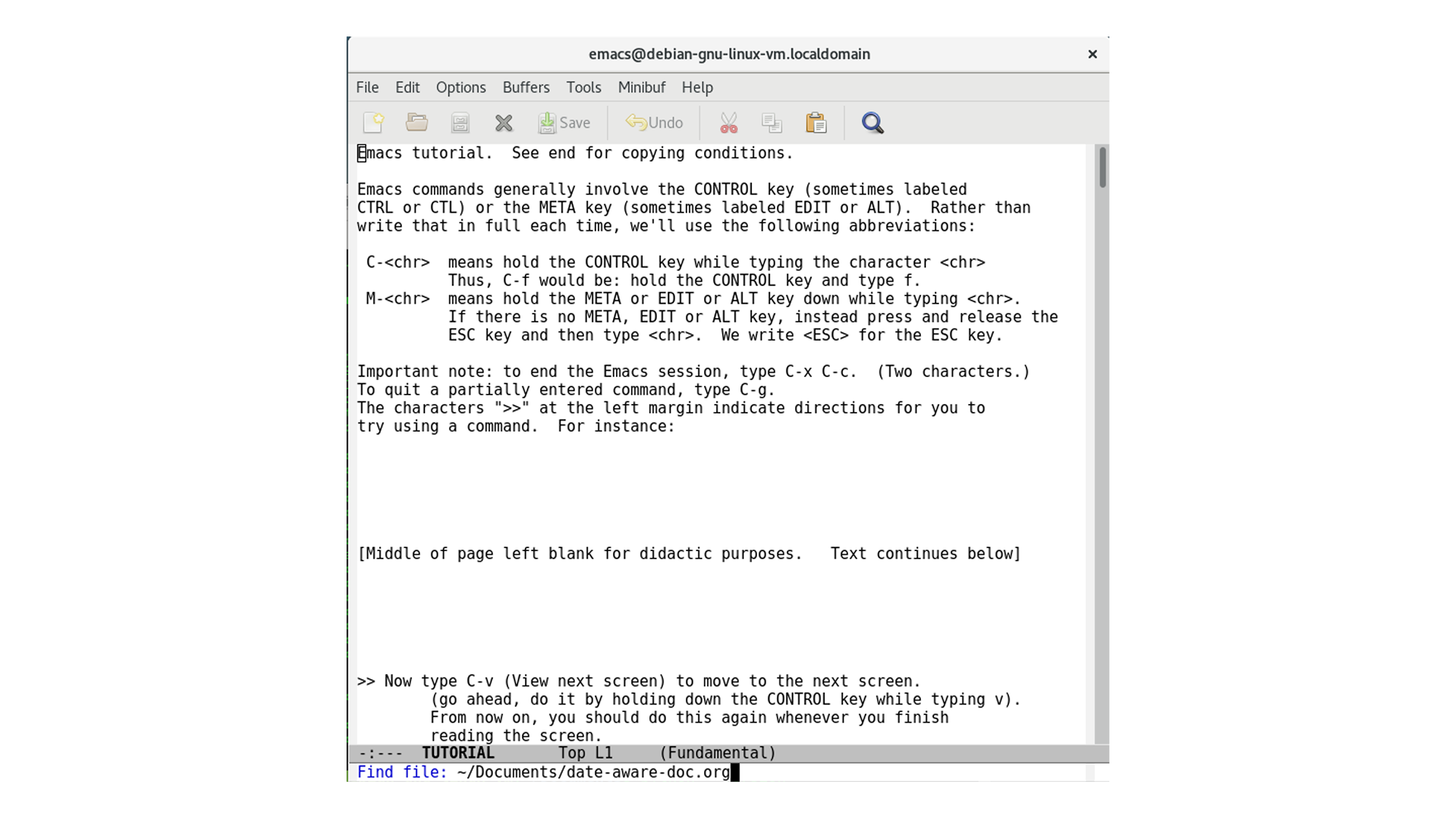

To create a file, you access the same function you'd used to open one: 'find file'. Press C-x C-f (that's Emacs notation for keeping the CTRL key pressed down while pressing x and then f). Notice the line at the bottom of the screen now says Find file:. This line is called the minibuffer and it's a way to interact with Emacs directly. It will show you a directory path. Edit it to point to the place where you want to create the file, which we'll call date-aware-doc.org:

Hit enter and the screen will go blank. Don't panic - it's created the new file. The tutorial is still there, but it's in a different buffer.

Emacs uses a system of files, buffers, and frames. When you open a file on disk, it appears in a buffer, which is a portion of memory that lets you edit the text in the file. However, because Emacs actually predates modern graphical operating systems, what Emacs refers to as 'frames' are referred to by most software as 'windows'. By the same token, the equivalents of Emacs' 'windows' are more commonly known as 'panes' in other programs.

Each frame contains one or more windows, and each window displays a buffer. The classic command-line version of Emacs only allows you to have one frame open at a time, but with the GUI version, you can have multiple frames and buffers open at once.

Got that? Good; let's move on.

Press M-x b (that's Meta and x together, and then b on its own). See how the mini-buffer is asking to switch buffers? It defaults to the last buffer you used, which in this case is TUTORIAL. Hit return. There's your tutorial. M-x b and return again brings you back to date-aware-doc.

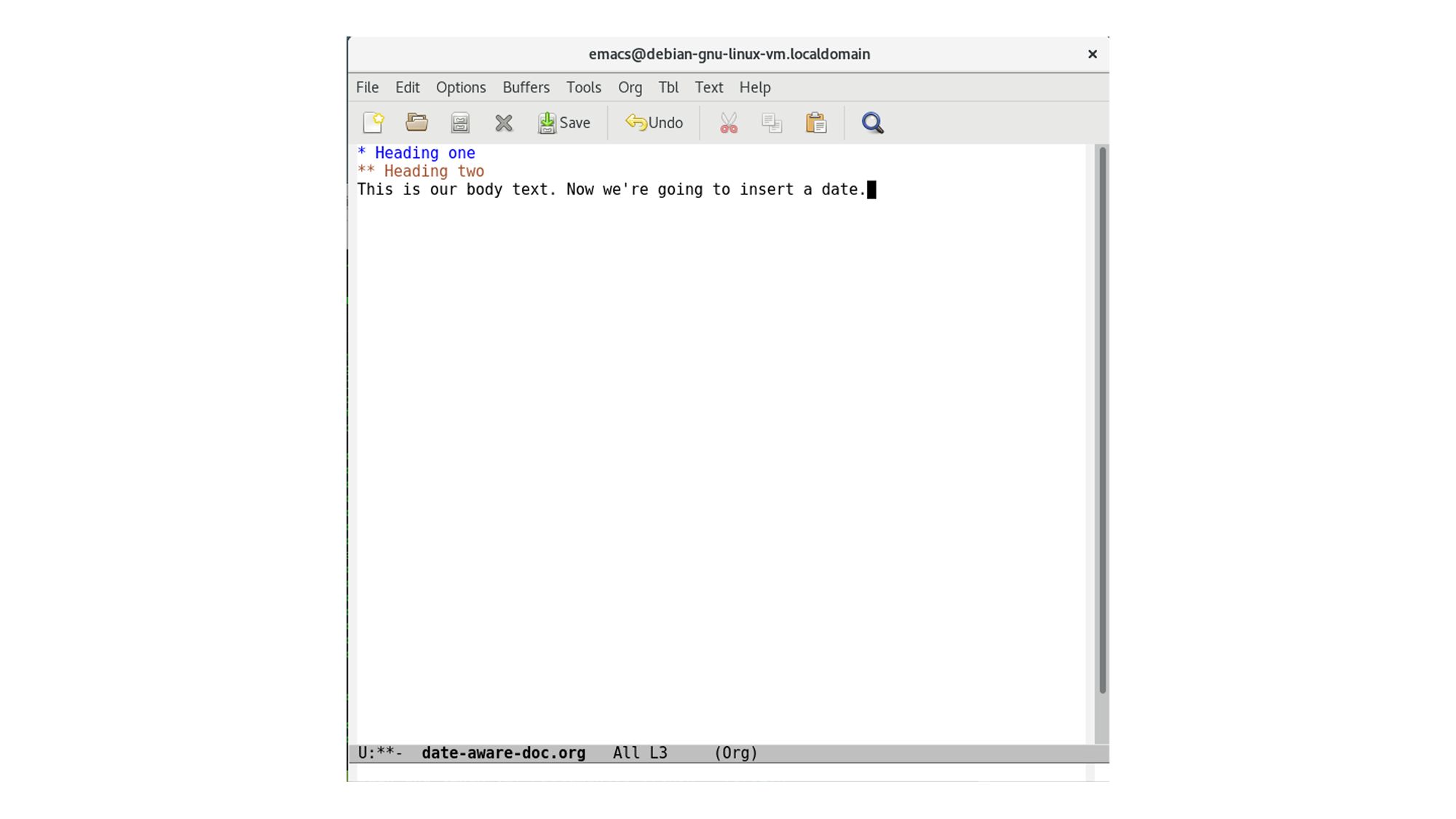

Now, type:

| * Heading one |

Don't forget the space. Then, press shift and return together. See how it begins the new line with an asterisk? Press M-Shift and the right arrow key together. Now there are two asterisks, and the second line is a different colour. Type:

| ** Heading two |

Then hit RET and add (without asterisks):

| This is our body text. Now we're going to insert a date. |

Because we used the .org extension for this file, emacs dropped us into org mode.

Each buffer in Emacs has a major mode that defines its operation. There are modes for programming in Python or C, for example, and for text editing. Major modes replace each other (you wouldn't use Python and C modes together) but you can extend major modes with minor modes. Abbrev-mode expands text based on a predefined list of abbreviations, for example, while display-line-numbers mode inserts line numbers next to your text.

Org mode is one of the most popular built-in emacs modes. It's an outliner that includes a gaggle of other organisation features, including to-do lists and a calendar.

Emacs tells you what mode it's using in the mode line, which is the single line just above the minibuffer. In brackets, you should see (Org):

Now we're going to help the document work out what date it is and insert it into its own text. This needs a code block, which emacs runs directly in the document using a minor mode called babel.

On a new line at the foot of your text, type and then press TAB. It expands into the beginning and end of a source block. Tell it what language we're using by typing python after the beginning of the source block's opening line. Then, in the middle of the block, insert this simple Python code:

| #+BEGIN_SRC python :exports resultsimport datetimecurrentDT = datetime.datetime.now()return currentDT.strftime("%a, %b %d, %Y")#+END_SRC |

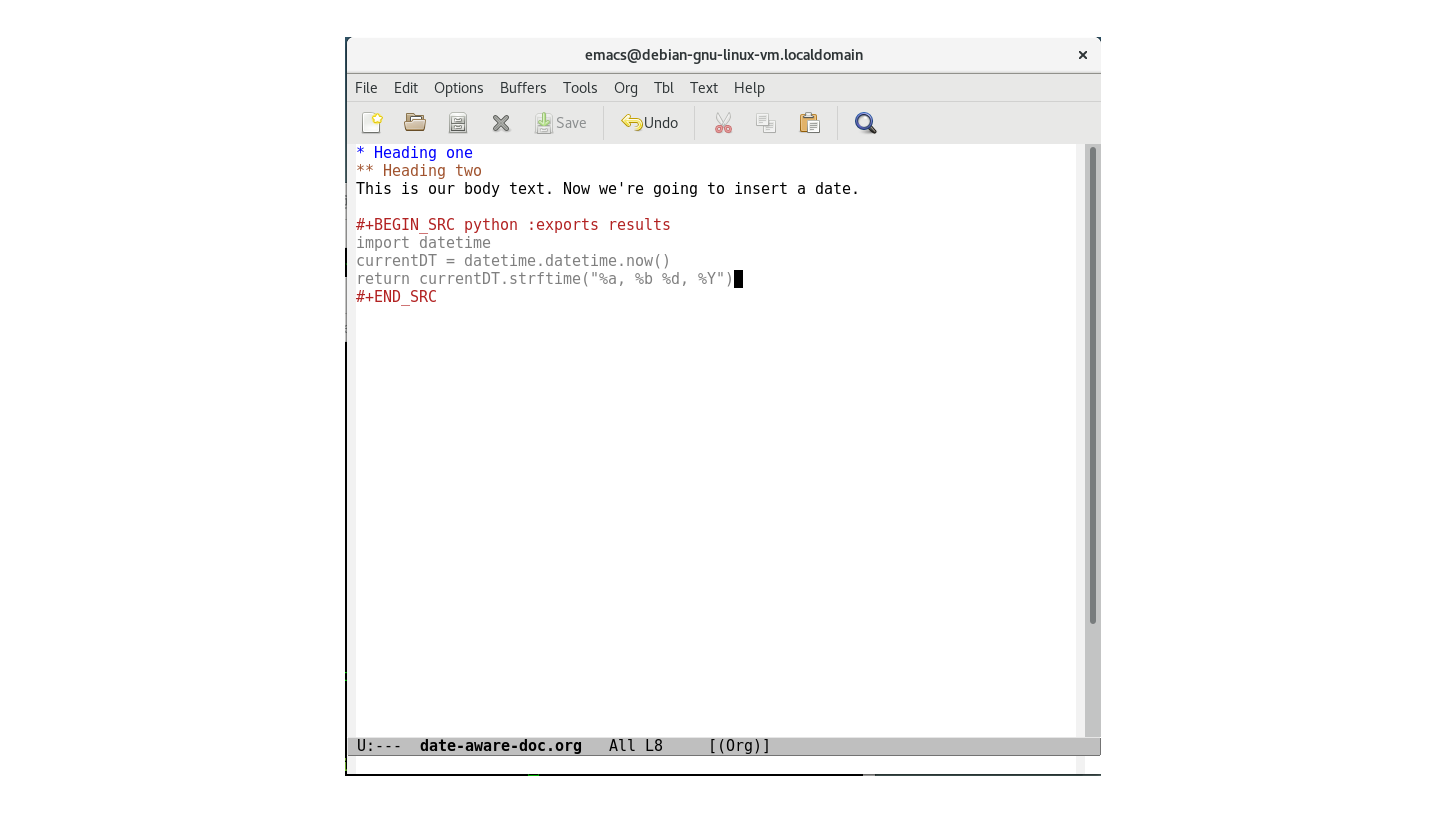

Your file should now look like this:

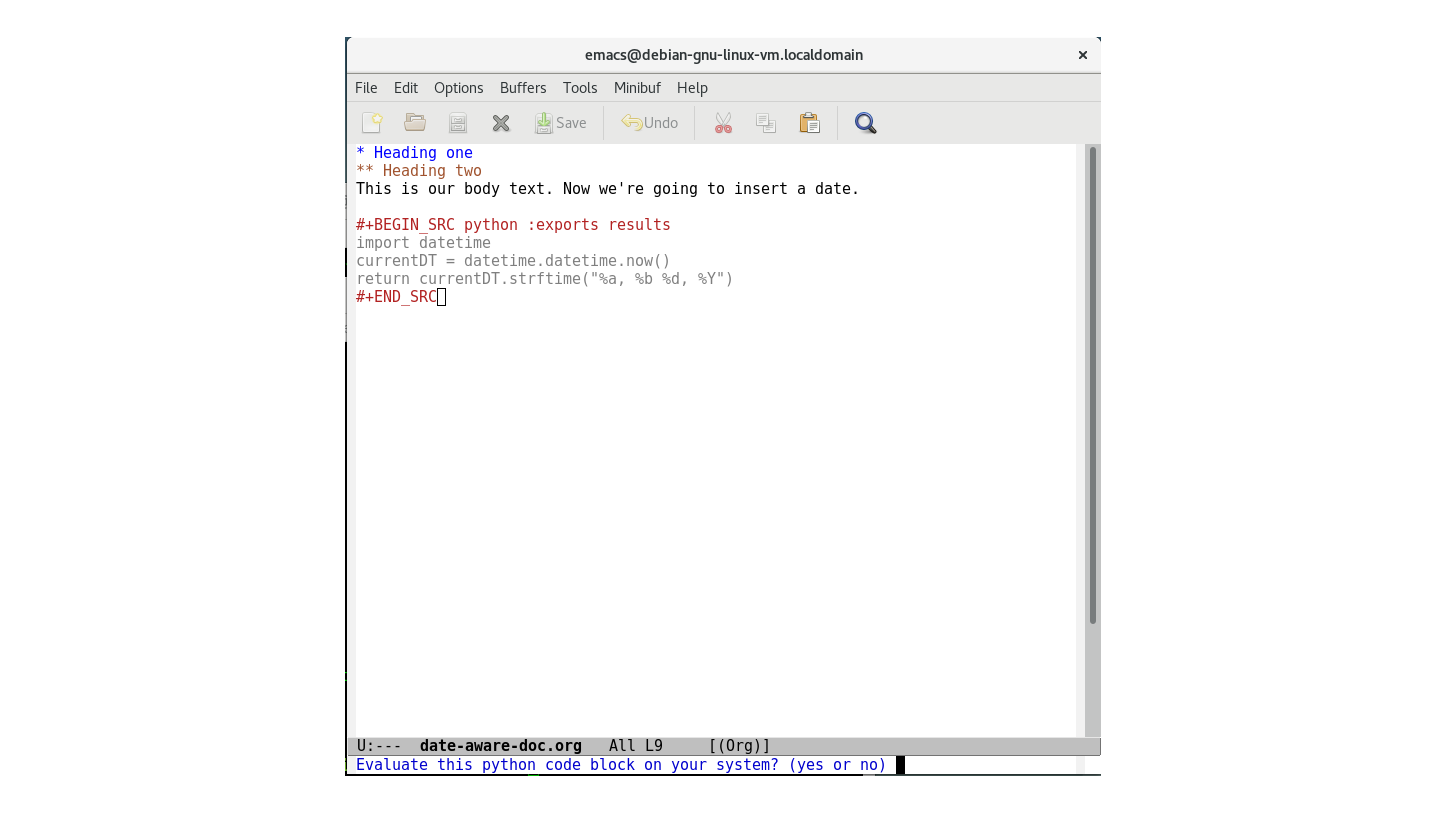

Test out the code by putting your cursor at the end of the last line of the above code in your document and pressing C-c C-c to execute it. Now you should see this:

It's asking you if you really want to run the code in that SRC block. This is a security check, because executing untrusted code in a document can do bad things to your system. This code doesn't pose a risk, so type yes.

Oh no! We have an error message: no org-babel-execute function for python! Emacs is telling us that org-babel doesn't know how to run this code. We're going to have to configure it. So hit C-g to quit the current operation and let’s do that.

Emacs loads using a configuration file called init.el (the extension stands for Emacs lisp), which contains custom functions and settings such as key bindings and parameters for opening and formatting documents.

Depending on your implementation, you'll find it in a folder like .emacs.d/ under your home directory, along with the program's other underlying files. Create it now by hitting C-x C-f and then entering the path. It will vary depending on your OS, but in Linux and MacOS use this:

| \~/.emacs.d/init.el |

Now, copy this Emacs Lisp code into your document:

| (org-babel-do-load-languages 'org-babel-load-languages '((python . t))) |

Save this (C-x C-s), close it (C-x C-k then RET), and then exit Emacs by closing all buffers at once (C-x C-c). When you restart Emacs, it'll process that file. Then, open your date-aware-doc.org file using C-x C-f.

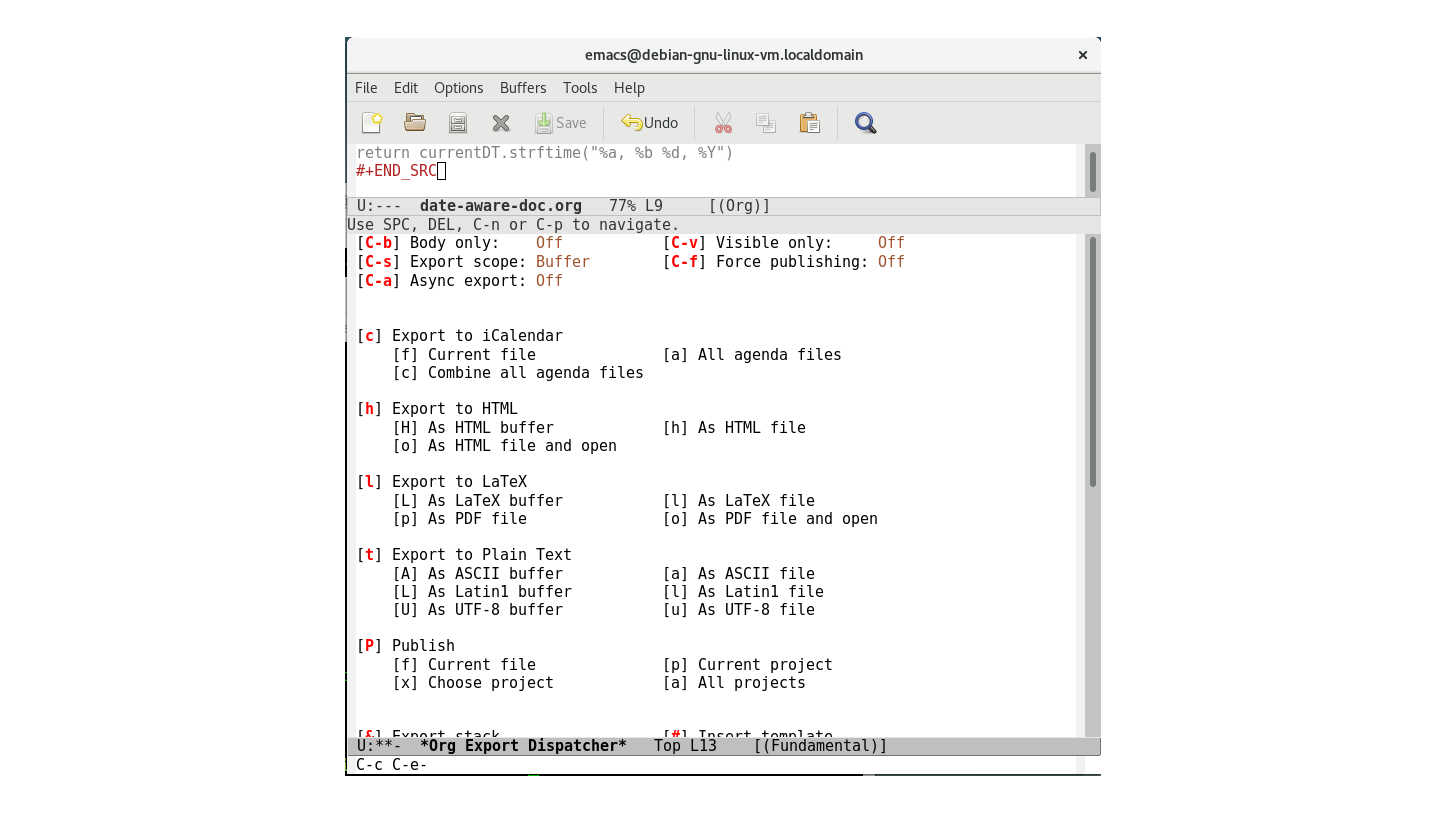

Now, it's time to export the document. Luckily, org mode has its own built-in exporter. Hit C-c C-e to bring it up:

As you can see, we can choose a variety of file formats to export to, but we're going to keep it simple and export straight ASCII text. Instead of exporting to a file, we'll export directly to an emacs buffer. Hit t to export to plain text, and then A to export to the buffer (don't ignore the capitalisation, it's important).

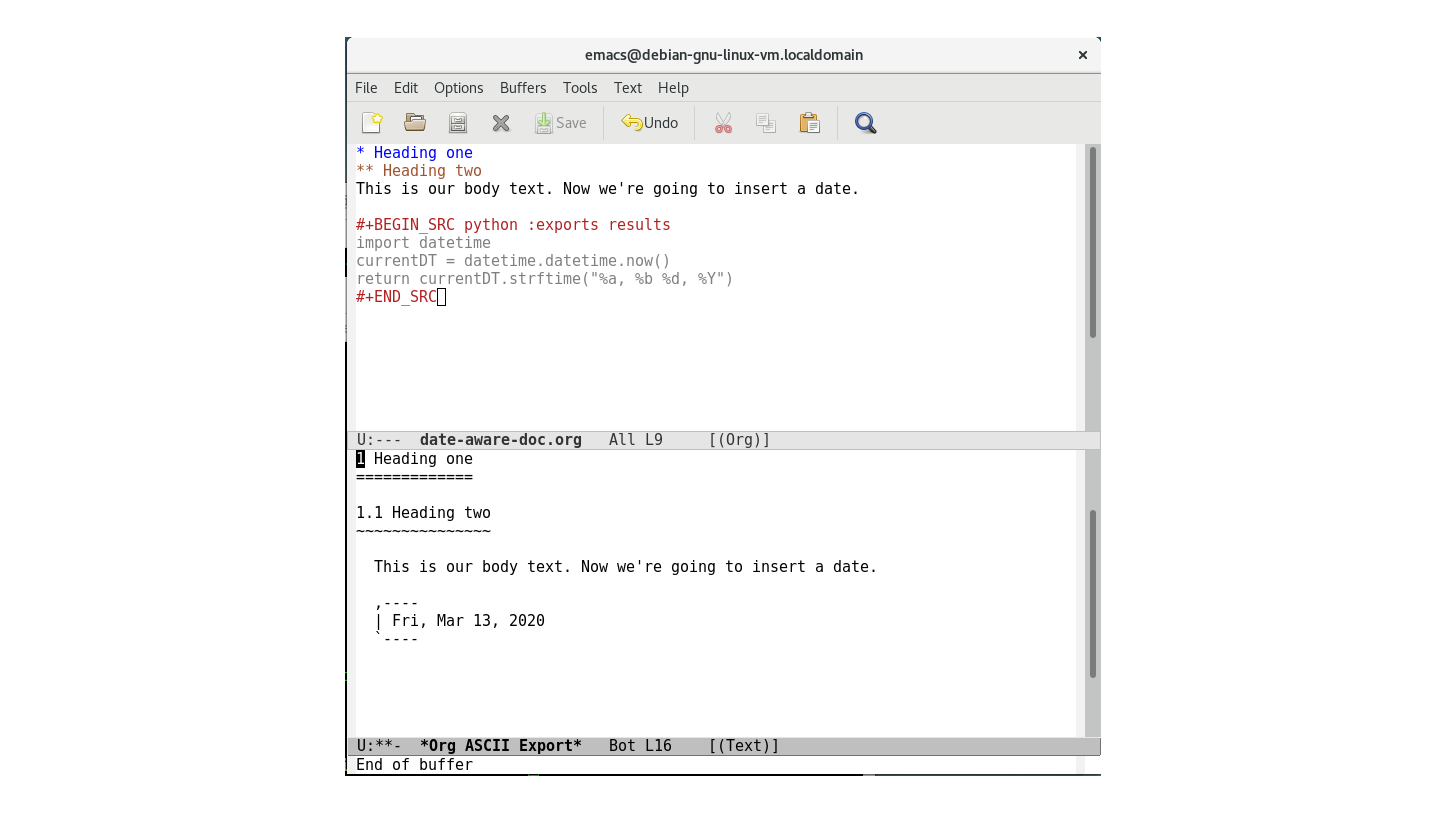

You'll see a new emacs buffer appear with a title and the heading text that we typed earlier, but numbered (emacs has formatting rules that we can change, but that's for another day). Scroll down and you'll see today's date inserted in your document:

So, that's emacs. It should be clear by now that it isn't a straightforward text editor, You might call it an operating system that thinks it's a text editor. Or a text editor that thinks it's an operating system. It's complex, difficult to learn, hard to configure, deliberately unsexy, and insanely powerful. Just one warning: If you're going to try it, allocate a month or two to learn it properly. It'll slow you down at first, and you'll feel like you're trying to eat peas with chopsticks for a while, but once you grok it you'll never look back.

Danny Bradbury has been a print journalist specialising in technology since 1989 and a freelance writer since 1994. He has written for national publications on both sides of the Atlantic and has won awards for his investigative cybersecurity journalism work and his arts and culture writing.

Danny writes about many different technology issues for audiences ranging from consumers through to software developers and CIOs. He also ghostwrites articles for many C-suite business executives in the technology sector and has worked as a presenter for multiple webinars and podcasts.