Should employees be microchipped?

With the UK now becoming a target for the microchipping craze, we assess its feasibility as a business tool

Microchips are a fact of modern life. They are in our washing machines and coffee makers, our cars, credit cards, even our cats and dogs.

The technology has proven so successful that some of questioning whether microchips could work just as well in our own bodies. It's still a somewhat faddy concept, but people are increasingly turning to miniature technology, whether it's to provide an alternative to carrying identity cards or just to realise their cyborg fantasies. It's not just an international craze either we're now starting to see a swell of interest in the UK.

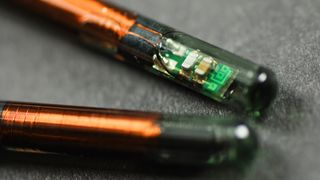

Swedish firm Biohax International has been implanting a passive, near field communications (NFC) device into humans for some time in its native land. The device is tiny 2mm x 12mm and it is certified to retain data for ten years. The chips are implanted into the hand and allow users to wave at readers in much in the same way as a contactless bank card or security pass. The installation process is said to be relatively painless no more or less painful than a piercing.

Now the Swedish export has made its way to the UK. Biohax has said it is seeing interest from UK firms looking to use personal chips, while BioTeq, one of a number of UK-based firms, has started to offer a range of implant services from as little as 39.95.

Reports suggest around 3,000 people have so far been chipped in Sweden, where the technology is being used in partnership with SJ Swedish railways as an alternative to tickets, reducing waste paper and replacing plastic travel cards. Biohax cites many other uses including gym access, digital business cards, even starting up the coffee machine.

Big Brother technology

While the tech could be seen as an overly invasive solution to the problem of multiple identity cards, businesses are starting to see the benefits of creating an 'always online' workforce, creating an opportunity to track employees through something other than the devices they use.

Amazon has already patented a wristband that can track a worker's movements around its warehouse, sparking fears that detailed monitoring of their speed and efficiency could be tracked. For example, if companies go a step further and provide workers with chip implants, employers could then know when workers arrive and leave, and even how long they spend at the water cooler or in the loo.

Get the ITPro. daily newsletter

Receive our latest news, industry updates, featured resources and more. Sign up today to receive our FREE report on AI cyber crime & security - newly updated for 2024.

This is part of a much wider issue of workplace monitoring. As Richard Edwards, service director & distinguished research analyst at Freeform Dynamics, explained to IT Pro: "Most of us carry around a tracking beacon when we're at work. It's called a mobile phone. These could easily be used to track employees as they go about their day."

However, unlike a mobile phone, the chip would be constantly operational and would be free of issues that may otherwise interrupt the collection of data, such as a device being switched off or running out of battery.

Trades Union Congress general secretary Frances O'Grady has expressed concerns about chip implants, saying in a statement: "We know workers are already concerned that some employers are using tech to control and micromanage, whittling away their staff's right to privacy. Microchipping would give bosses even more power and control over their workers."

For O'Grady, the way forward is all about discussion and diplomacy. "Employers should always discuss and agree workplace monitoring policies with their workforces. Unions can negotiate agreements that safeguard workers' privacy, while still making sure the job gets done." She added that the "law needs to change too, so that workers are better protected against excessive and intrusive surveillance".

Yet another tool in 2FA

Chips currently don't carry much data. But their capabilities will grow, and with them so will the question of data security. "I wouldn't count on chips alone," says Edwards. "Most security conscious organisations seem to favour a multifactor approach to authentication and security even though it can be costly to implement and manage."

Implant chips certainly shouldn't be left in sole charge of the security of the information they contain, but could be combined with a second personal biometric such as a fingerprint or a PIN. "We know that chips can be read and cloned, so any use would have to be part of a multifactor approach to identity and authentication," says Edwards.

In the end, whether we like it or not, it seems the age of the personal chip has arrived. The challenges we face now are similar to those we face in other areas of technology preventing misuse and ensuring data security.

Chips bring their own special challenges too. Much like other medical implants, there's a need to ensure the chips themselves, and the processes used to insert and remove them, are medically safe.

Sandra Vogel is a freelance journalist with decades of experience in long-form and explainer content, research papers, case studies, white papers, blogs, books, and hardware reviews. She has contributed to ZDNet, national newspapers and many of the best known technology web sites.

At ITPro, Sandra has contributed articles on artificial intelligence (AI), measures that can be taken to cope with inflation, the telecoms industry, risk management, and C-suite strategies. In the past, Sandra also contributed handset reviews for ITPro and has written for the brand for more than 13 years in total.