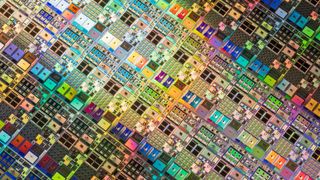

Semiconductor shortage will likely last until 2025, expert claims

Ondrej Burkacky says investment in the sector cannot yield results in the short term, and government spending is not a silver bullet

The global semiconductor supply chain may be unable to return to normal operation until at least 2025, one expert has claimed.

Since 2020, the semiconductor industry has faced lingering disruption, initially sparked by a slow down in manufacturing during the height of the pandemic.

At its nadir in January, the United States was said to have less than five days worth of semiconductors in its stockpile. In the two years since, semiconductor manufacturers have looked to ramp up production, but some in the field say this won’t help in the short term.

“So it still takes you a minimum of three years to ramp up a new semiconductor facility,” said Ondrej Burkacky, senior partner at McKinsey’s Semiconductor Practice, speaking on the IT Pro Podcast.

“And that's already a pretty short timeframe; in many geographies, it's more like five years that it takes you to get all the approvals to construct it, to bring in the tools to ramp up to a full yielded product.”

Given the length of time that it takes to get semiconductor sites planned, built, and put into operation, manufacturers are also faced with a great deal of uncertainty over the demand of the market they will be selling to down the line. The sudden impact of the pandemic took most of the world by surprise and didn’t fit into business projections, and similarly impactful crises such as the invasion of Ukraine or the increasing cost of living crisis make markets uncertain.

“When you have such timeframes, like three to five years to build out a product production facility, you need to be damn sure that you have the demand in place," said Burkacky.

Get the ITPro. daily newsletter

Receive our latest news, industry updates, featured resources and more. Sign up today to receive our FREE report on AI cyber crime & security - newly updated for 2024.

This outlines the high risks for semiconductor manufacturers investing today, who need to accurately predict demand several years down the line to inform current decisions. Despite this, Burkacky states that businesses that correctly anticipate this demand and play into the right markets could come out on top come 2025.

“So this can take well into 2024 or even 2025 until this gets fully sorted out. But there are ways for players to optimise their sourcing, there are ways for them to commit to more longer term supply agreements," said Burkacky.

“I think going forward, while there still might be a certain shortage, there will be ways for players to excel here and be able to source the semiconductors they need, versus others who might still struggle.”

Automotive manufacturers responded to the unprecedented low demand for cars during the worst months of the pandemic by cancelling large orders of chips, and weathered huge losses in 2021 as a result. Only now is it re-establishing chains to return to pre-pandemic production levels, and is limited by the same turnaround as any other semiconductor production.

“One of the reasons why the automotive industry got struck so hard by the chips shortage is because they had basically no inventory along the entire value chain that they could survive from,” noted Burkacky.

Seeking to ease the supply strains experienced by the industry, a number of governments have looked to subsidy packages for semiconductor manufacturers. The US recently passed the CHIPS for America Act, which provided approximately $54 billion in subsidies for chip factories such as Intel’s proposed site in Ohio.

Just last week, Intel further announced $30 billion plans to expand its Arizona chip plant, citing the importance of robust supply.

The EU is also moving forward with its own Chips Act, which is expected to provide up to €43 billion to further safeguard semiconductor supply on the continent. Geopolitical tensions between the US and China have also led the latter to move towards consolidating its domestic semiconductor supply chain.

A recent US trip to Taiwan, to discuss the passage of the CHIPS act with Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) resulted in a flurry of cyber attacks on Taiwanese government websites, originating from China and Russia.

In a final word of warning from Burkacky, he acknowledged that although government investment is clearly driving investment from some companies, it will not accelerate overall supply chain recovery.

"Just because you have a Chips Act in place doesn't mean that the day after there is no more shortage, right? As I said before, there is still the physics of three to five years to build a semiconductor plant.”

A full interview with Ondrej Burkacky can be heard on the IT Pro Podcast.

Rory Bathgate is Features and Multimedia Editor at ITPro, overseeing all in-depth content and case studies. He can also be found co-hosting the ITPro Podcast with Jane McCallion, swapping a keyboard for a microphone to discuss the latest learnings with thought leaders from across the tech sector.

In his free time, Rory enjoys photography, video editing, and good science fiction. After graduating from the University of Kent with a BA in English and American Literature, Rory undertook an MA in Eighteenth-Century Studies at King’s College London. He joined ITPro in 2022 as a graduate, following four years in student journalism. You can contact Rory at rory.bathgate@futurenet.com or on LinkedIn.