Project Soane: how VR can help bring back history's lost treasures

One of London's most important lost buildings has been resurrected - thanks to virtual reality

History is important; it reminds us of our heritage and provides a foundation on which future generations can build. But what happens when that history is lost to the ages? Historical buildings or landmarks can be destroyed by war, by natural disaster, or simply by the relentless march of progress.

When that happens, it usually survives only in historical record, but at least one architecturally significant site has been rescued from oblivion - thanks to the magic of virtual reality.

The Bank of England is one of the world's oldest and most respected financial institutions (up until June 2016, at any rate), but the building itself is actually less than a century old. Prior to the 1920s, the country's central bank was housed in a building designed by legendary architect Sir John Soane, who worked on it for over four decades.

Soane has become one of architecture's most respected figures, and the bank was considered to be one of his greatest achievements, featuring extensive classical features and use of natural light. The demolition of his work in 1925 to make way for a larger, more modern space is now regarded as a travesty, and academic Nikolaus Pevsner called it "the greatest architectural crime ... of the twentieth century".

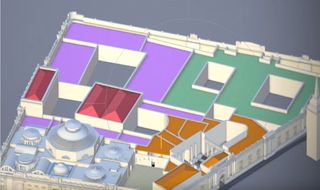

HP agreed, and launched a project in 2015 to try and digitally recreate Soane's Bank of England with the help of New York firm Robert A. M. Stern Architects (RAMSA). The project had two stages, with the first being to recreate the bank using BIM modelling, a digital design technique used in modern architecture.

Luckily for present-day architectural historians, Soane kept a great deal of detailed notes relating to his work, including 3D models, illustrations and blueprints. Under the watchful eye of RAMSA, these documents were then transformed by crowdsourced volunteers into Autodesk Revit models.

"The Bank of England is vast and complex, and even with the cache of archives his will left for us, it's too long and challenging for a lone scholar," said RAMSA partner Melissa Del Vecchio, "but it's completely suited to a crowdsourced effort."

Get the ITPro. daily newsletter

Receive our latest news, industry updates, featured resources and more. Sign up today to receive our FREE report on AI cyber crime & security - newly updated for 2024.

Andy Milburn, an architect and BIM expert who worked extensively on the project's first phase, noted that the process of BIM modelling bears some striking similarities to Soane's original design methodology, particularly his use of physical models and architectural drawings by Joseph Gandy.

"What struck me was that there's a very close parallel with the way we work now with BIM," he said, "because we have these default 3D views ... but we also have these set-piece camera views that we set up, which is trying to get a sense of 'OK, what would it feel like to be in that space?' And that's starting to move to VR as well now. In a way, that's the same kind of thing he was doing with Joseph Michael Gandy."

The second phase of the project was a competition, where architects, designers, renderers and others could use the completed models to produce digital renderings of what the building would look like if it still survived today. The contest included multiple formats and categories, including video, still images and real-time experiences that used cutting-edge VR to place users inside a virtual reconstruction of the original bank.

Looking around the virtual interiors of the various bank buildings, you may be tempted to wonder what all the fuss is about - after all, it's just a bank interior, and the experience doesn't really compare to some of the more thrilling VR experiences out there. However, look at the big picture and the significance becomes clear.

This building - though not necessarily the most immediately exciting to the average person - is hugely important to architectural history and for the first time since its demolition, students of Soane's work can experience it in person, the way he originally intended. "We'll always be great big fans of the work of Soane," Karam Bhamra, a CGI designer who worked on architecture firm Hoare Lea's category-winning VR experience, told IT Pro.

"This idea of being able to put yourself back in the space and experience it a hundred years after it's gone, see what it would have felt like - and not just see how it was, but then also see how it could be today - that was something that really resonated with us."

In fact, Milburn told IT Pro, the whole recreation process can be used in education to give architecture students a much more in-depth understanding of how Soane's buildings worked on a technical level. "I would hope it would be used to involve students. I think the really great thing for architecture students would be for them to become hands-on," he said.

"Not just walking through the space - that would be great as well - but for them to be asked to take a small part and recreate it," Milburn continued. "My experience on the project has been that being really hands-on and setting problems to yourself, that's where you really start to learn a lot more than reading books."

"I think it's a brilliant way of letting people experience lost architecture," Bhamra told IT Pro, explaining that for many of history's forgotten buildings, recreating them would simply be impossible. "The talent that was there when they made buildings like this... you just wouldn't be allowed to make something like that any more."

It's not just Soane's Bank of England that can be brought back into the present, either. This same technique could potentially be used to digitally restore countless lost architectural and historical wonders. Even something as ancient as the Parthenon, Milburn said, could be rebuilt in VR - it all depends on how much documentation there is.

"Obviously, [it's] still partly there, so you could probably figure out quite a lot of the Parthenon. People have measured [it] in the past; there must be quite a lot of documentation around. It would be a challenge to trace it all down and put it together, so I think that's a big part of it - how you get that stuff. But there must be photographic records of quite a lot of buildings that have been demolished; photography goes back a hundred years."

However, undertakings like Project Soane require a considerable amount of investment, not to mention time and manpower, and HP Inc. is unlikely to sponsor the reconstuction of all of history's forgotten buildings. Thankfully, Milburn has some ideas as to who could pick up the baton.

"I think academic institutions, schools of architecture and so on, should get more involved with this kind of thing. They have some of the money to put in, but also they've got the academics who can do the quality control and they've got the labour force - they've got students who would learn a lot from it and could do a lot of the work."

While it may be an instrument of the future, it seems that VR can also help us recapture the past, and the fact that Soane's Bank of England - once thought lost to time - has been resurrected is inspirational, as RAMSA partner Graham S. Wyatt notes. "Recapturing what it was like to walk through its spaces has become a persistent dream for me and many others," he said. "I'm confident Sir John Soane would have been impressed."

Adam Shepherd has been a technology journalist since 2015, covering everything from cloud storage and security, to smartphones and servers. Over the course of his career, he’s seen the spread of 5G, the growing ubiquity of wireless devices, and the start of the connected revolution. He’s also been to more trade shows and technology conferences than he cares to count.

Adam is an avid follower of the latest hardware innovations, and he is never happier than when tinkering with complex network configurations, or exploring a new Linux distro. He was also previously a co-host on the ITPro Podcast, where he was often found ranting about his love of strange gadgets, his disdain for Windows Mobile, and everything in between.

You can find Adam tweeting about enterprise technology (or more often bad jokes) @AdamShepherUK.