Context-aware computing is here – and it's getting smarter

Alexa knows when you're getting ill and researchers are listening using vibrations

Alexa," you say to your home voice assistant, coughing as a cold starts to catch up to you. "I'm hungry cough what recipe should I cough try?" Alexa suggests some chicken soup, and asks: "By the way, would you like to order cough drops with one-hour delivery?"

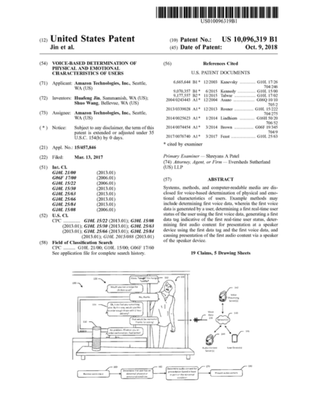

That's the future of context-aware computing that Amazon envisions with its Alexa voice assistant, according to a recently filed patent application. Not only will Alexa be able to translate your coughs, sniffles, sneezes and wheezes into symptoms of a cold, but it will also consider your "emotional condition". It will then detect whether you sound sad or excited so it can "determine relevant audio or visual content for presentation to the user," in the dry language of the patent filing.

The idea behind context-aware computing isn't to simply analyse one aspect, such as a cough in a voice: Amazon's filing suggests it's also considering listening to background sounds as well as using a combination of behavioural targeting criteria, including your browsing history, what pages you click on and what you buy. That's no surprise that sort of algorithmic stalking is Amazon's modus operandi, after all but with smart assistants slipping into our homes, voice controls in our cars and smartphones in our pockets, the data collection is increasing.

Amazon's context-based patent suggests Alexa can determine your "emotional condition"

For example, carrying a smartphone everywhere and using it to plan a journey lets Google Now make proactive suggestions, notifying users that they should leave for work a bit earlier because there's traffic on their normal route. That requires knowing not only where your home and workplace are, and how you commute, but also pulling in external data from transport providers.

As more and more data is collected, such systems become increasingly powerful. "There's a lot of new data that's coming in," said Erick Brethenoux, an analyst with Gartner. "It's linked to the Internet of Things, to Fitbit and all these different wearable devices, and... clothes with sensors built in. We can see that there's a lot more data that allows us context."

Any system that's making assumptions about our mental or emotional states will make mistakes, of course. Amazon may assume a listener is streaming a playlist of sad songs because they're emotionally low, but if it can listen in via your speaker then it may realise you just really like singing along to melodramatic power ballads while cleaning the kitchen. More data means more context, so rather than suggest gin on one-hour delivery, Amazon may instead proffer tickets to a local karaoke night.

Get the ITPro. daily newsletter

Receive our latest news, industry updates, featured resources and more. Sign up today to receive our FREE report on AI cyber crime & security - newly updated for 2024.

Context and costs

Context-aware computing can be helpful, but it can also be intrusive. As ever, companies using such techniques need to be wary of privacy.

"Every single application needs to have an explicit opt in," said Brethenoux. "You need to be aware of what information is gathered about you, how it is going to be used, and how long it's going to be kept. You have the right, of course, to modify, delete and stop it at any time."

The Vibrosight project uses lasers to identify when you're doing activities such as walking on a treadmill

That will help to assuage concerns, but Brethenoux notes that developers should always be careful of how people react to such technologies.

"We have to be very sensitive to the impact that this has on people and not make assumptions."

Context-aware computing can be more useful than simply boosting your spending. Brethenoux gives an example of an insurance company in Chicago that notifies customers of extreme weather events such as hail, considering the context of whether that customer lives in an affected area and owns a vehicle.

"If they are in the path of the storm, the company can send a text telling them to move their car somewhere protected in the next ten or 15 minutes," Brethenoux said. "Hail causes tremendous damage [to cars]."

Insurees aren't punished for failing to bring their car under cover, but it helps the company avoid some damage payouts, meaning it can keep costs down.

Cutting down on tech

And Brethenoux argues that context-aware computing, if used well, could actually reduce our use of technology.

"I think those techniques, such as context-aware, should be used not for more communication but for less communication," he said. "Those things should actually free us... we're tired of being buzzed and beeped at to death, because it's constantly coming at us. Why don't we use context to diminish the number of notifications?"

For example, Alexa could understand from what it can hear that you're in a meeting, or having dinner with family, or enjoying a bit of peace and quiet, so opt not to interrupt you. Or context awareness could be used for simple, helpful tasks. Some smart TVs controversially have cameras in them to look at who is sitting on the sofa watching, for example to target advertising. That camera could be used to see if someone is even watching anymore, and if not and the time is late, perhaps switch off the TV entirely, rather than leave it on standby.

Context could help make computing more helpful, Brethenoux added. "It's linked to another concept in computing that is starting to see a resurgence called 'software agents'," he said. "They are self-contained programmes that can do a few simple tasks on your behalf."

Those agents can use context awareness to know when we need to see a message or notification, and when we don't. "I think it's important to be able to get the right things at the right moment, and sometimes decide not to act," said Brethenoux.

Tech that actually knows when to shut up? That's a skill we would love Alexa et al to have.